More on Labs

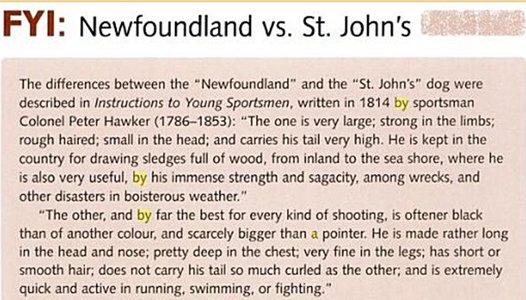

Newfoundland vs. St. John’s produced two distinct types of dogs: the Newfoundland, a larger dog that assisted with fishing tasks and pulled carts; and a smaller dog that also assisted with fishing tasks but could serve as a good gundog, too. The form that began to take shape for the island’s smaller, working retriever included qualities that made the dog a good swimmer (broad chest, buoyant body, and webbed feet), and a resilience to a cold water (an efficient distribution of body fat, as well as a thick, water-resistant double coat).

Another physical feature of the dog that began to appear was that of an “otter” tail. Rather than having a tail that was held curled over the back, the Retriever from Newfoundland had a rudder-like tail: thick, shorter (more of a three-quarter-length tail), mostly straight and held lower. Early records note that the retriever was primarily black in color and was sometimes referred to by many names, including St. John’s Water Dogs or Little Newfoundlers. As word spread of the abilities of the black retriever from Newfoundland, sportsmen in England sat up and took notice.

The exact date that St. John’s Water Dogs were first imported into England isn’t known; however, early records indicate that sometime between 1825 and 1830, dogs were received by the Fifth Duke of Buccleuch, his brother Lord John Scott, the Earl of Malmesbury, the Earl of Home, and a Mr. Radclyffe.

The imported St. John’s dogs were so highly valued that by 1880, it is estimated that more than 60 gamekeepers were training and looking after Labrador Retrievers on different estates in England.

However, the supply of St. John’s dogs was soon to be all but cut off. Newfoundland inaugurated a Sheep Protection Act, which imposed a duty on all dogs, so fewer people could afford to keep and breed dogs. Added to this problem, England initiated its Quarantine Act. So, by 1885, not only had the number of St. John’s dogs dwindled severely in Newfoundland, but it was far more difficult (if not impossible) to import dogs into England.

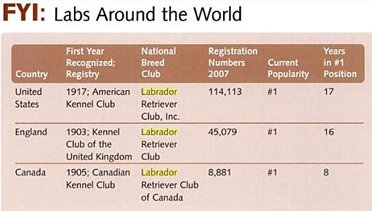

The breeding and future of the Labrador Retriever now lay in the hands of England. Thankfully, dedicated British sportsmen and dog fanciers continued to breed and refine the Labrador. In 1903, the breed was recognized by the Kennel Club of the United Kingdom.

Interestingly, in the early days of dog showing, retrievers used to be exhibited in Kennel Club shows together. In other words, there were no separate classes for Golden Retriever, Flat-coated Retriever, Curly-Coated Retriever, or Labs. Rather, dogs were shown in a retriever class by their coat type (ie, flat, curly, etc.). It wasn’t until 1905 that the Labrador was recognized as a separate breed and classified as a “sub-variety” of retriever.

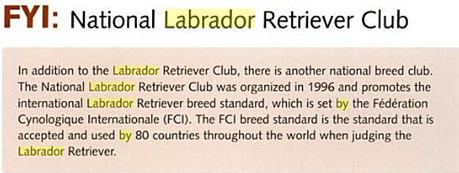

Of course, this classification still had its issues, as dog owners were allowed to register their dogs under the breed that it most closely resembled – whether or not the dog was pure Labrador Retriever, mostly Lab, or another retriever breed entirely. To sort this out, the Labrador Retriever Club was founded in England in 1916 and a breed standard was drawn up that outlined precisely how the Labrador was to look and move, and what its characteristics and temperament traits were to be. This breed standard has undergone few changes in the past 90-plus years, mainly to further clarify and more fully describe the original description.

Word of the talented Labrador Retriever quickly spread to sportsmen in America and Canada. Two years after the Labrador Retriever was recognized as a sub-variety of retriever in England, the Lab was recognized by the Canadian Kennel Club (CKC). Twelve years later in 1917, the Labrador was recognized by the American Kennel Club (AKC).

It’s hard to imagine that the breed that is enjoyed and treasured today by more people than any other was once owned and bred by so few in the United States. The gentlemen’s sport of shooting, made popular in Scotland, became a passion among America’s elite in the 1920’s.

Wealthy individuals would not only import Labrador Retriever from English kennels, but would also bring over young Scottish gamekeepers to help develop and run shooting preserves on their sprawling estates.

Though the number of Labrador Retriever in the United States was very low initially, the Labrador Retriever Club, Inc. was formed in 1931. It was in that same year that the first AKC-sanctioned field trial was held.

The superb hunting abilities of the Labrador attracted a wide following, and it wasn’t long after those first field trials were held in the United States that American sportsmen gained a keen interest in the breed. From the late 1930s to the late 1970s, the Lab enjoyed a gradual, controlled climb in popularity and was a favored breed among competitive field trailers as well as those seeking an excellent personal hunting dog. The Labrador Retriever was also quite successful in the show ring (conformation).

In the early 1980s, pet owners realized just how friendly, sociable and easily trained the Lab was. It was at this point that the Lab’s popularity sky-rocketed and the breed made the jump from favored retriever to favored household pet. Fortunately, the good-natured Lab proved to be highly adaptive and, for the most part, has per formed his most recent starring role as a pet very well.

Pet owners weren’t the only folks who realized the Labrador Retriever’s potential outside the marshes and fields. Service dog organizations that traditionally used German Shepherds for trained assistance dogs for the blind or disabled began to shift their breeding programs to include Labrador Retrievers. Today, roughly 60 to 70 percent of service dogs are Labrador Retrievers. The dogs are revered for their willingness to work, friendliness toward people, and high level of comfort in crowds and when presented with loud noises.

In the early 1990s the Labrador Retriever took on another role: top dog for arson detection. With the Lab’s excellent scenting abilities, the breed was chosen as the dog of choice for most of the country’s arson-detection programs. In fact, in some programs, the Labrador is the only dog trained for this purpose.

Use of the Labrador as a working, scent-detection dog grew. In 1999, the Transportation Security Administration (TSA) founded a kennel to breed its own Labrador Retrievers for explosives detection work. The program began with six adult female Labs and two adult males, selected specifically for their scenting abilities, trainability, work ethic, temperament, and health. Today the program produces nearly 300 trained Labradors annually for placement in the TSA program.

As other K9 programs expanded to include single-purpose dogs (the dogs were not required to perform patrol dog duties, such as apprehending criminals, and could focus strictly on scenting), more and more Labradors entered scent-detection programs for police, military and government agencies.

Working Labrador Retrievers are used to scent out everything from smuggled money, narcotics, illegally imported plants, and explosives to finding trapped or missing people, and serving in the recovery missions. Many of the search-and-rescue dogs employed in the aftermath of the 2001 terrorist attacks on the Pentagon and the Twin Towers in New York were Labrador Retrievers, working for volunteer SAR organizations, as well as police, fire-fighters, the military and other government agencies.

Upland game…waterfowl….blind and marked retrieves…gundogs….retrievers….If you are not familiar with the hunting world, these words may be a bit foreign-and as a result, the “job” that has evolved for the Labrador Retriever may be a bit of a mystery to the nonhunting pet owner.

A Lab is first and foremost a retriever. He fetches. While waiting by the hunter’s side, the good Lab watches the fall of a shot bird, “marking” its placement in his mind so that he knows precisely where to go when he is asked to retrieve it.

The Labrador Retriever is considered an excellent personal hunting companion; he embodies the best of all retriever characteristics and is equally strong retrieving on land as in water. To do his job well, the Lab was bred to have infinite patience (it might take a while to find a bird to shoot), terrific scenting abilites (allowing the dog to better find the location of a fallen bird or track a wounded bird), tremendous courage (necessary to forge through thick underbrush and jump unflinchingly into cold water), boundless energy (the dog needed to be able to hunt all day), and a strong, innate retrieving drive.

Labs come in three colors: black, yellow and chocolate. Historically, black has been the predominant color among Labrador Retrievers, and in the earliest days of the breed, it was also the most desirable color. White markings do appear on black Labs, particularly on the chest, toes, pads of the paws and chin.

Yellow Labs have been around for more than a century; the first registered yellow Labrador, Ben of Hyde, was born to an otherwise all-black litter in 1899 from the noted British kennels of Major C. J. Radclyffe. Yellow Labs range in color from a creamy, nearly white color to a very rich yellow with red-fox coloring. The Yellow Lab’s lips, nose and eye rims are black; however, a yellow Lab’s nose can get pinkish cast to it. Dogs that are born with black noess can lighten up with age and in colder climates; in rare cases, a yellow lab is born with a pink nose and has pink or chocolate coloring around the eyes (opposed to black eye rims). A yellow Lab without black pigment is called a Dudley, and cannot be shown in the breed ring.

Chocolate, a color that was reportedly present in St. John’s dogs, was first recorded in Labrador Retrievers in 1892 with a litter that was born to the Scottish kennels of the Sixth Duke of Buccleuch; however, it wasn’t until the 1930s that the color began to gain favor. Chocolate Labs can range from a café’ au lait coloring to deep liver colors, chocolate continues to be the least recorded of colors in the Labrador Retriever.

Occasionally, some rather wild color combinations occur in the Labrador Retriever. Remember, many breeds went into the development of the breed and every so often, if both parents have a recessive gene for a certain type of coloring lurking in their genetics, a surprising array of colors and markings might show up.

Referred to as “mismarks”, some of the unusual colors and combinations that can be seen in purebred Labrador Retreivers include brindles (also known as “splash”), tan markings (black or chocolate dogs with tan points), yellows with black spots, yellow and black dogs with a white ring around the tail, and even some dogs with larger mismatched colors, such as a yellow dog with a big splotch of black on the shoulder or a black dog with one yellow leg. It almost looks like someone splashed a bit of paint on the dog.

Though these variations in coat color are very interesting and very rare, they are not desirable and disqualifying traits in the show ring. However, the Labrador still holds its “goodness”.

The Labrador Retriever earned the number one position in the world because he is, without question, a great dog. Today’s Lab is not only tops as a family pet but continues to reign supreme as a retriever and personal gundog.

The Lab is also a top choice in police, fire, government, and military work as a detection dog, and in the private sector as a tremendous assistance and service dog.

The characteristics that have made the Labrador such a popular breed for the past several decades have not changed amount well-bred dogs: The classic Lab is intelligent and eager to learn, a tireless worker and a solid retriever, and possess a bomb-proof temperament. He is a dog that can adapt to a variety of living situations and is adept at participating in a huge range of performance events and outdoor activities.

The Labrador is a versatile, congenial dog of medium to large size that’s not huge, and definitely not too small. He is quite adaptable to a variety of living situations, and as long as he needs are met, the Lab can be a good fit in many homes.

Though the Labrador Retriever is most frequently seen as a pet, today’s Lab still possesses the genetics for all the abilities of his forefathers. Within the breed there is great variance as to the intensity of each individual Labrador Retrievers’.

Though the Labrador Retriever is most frequently seen as a pet, today’s Lab still possesses the genetics for all the abilities of his forefathers. Within the breed there is great variance as to the intensity of each individual Labrador Retriever’s abilities and drives; however, even Labs that haven’t been bred for field work in generations will still possess certain characteristics in common with their superior hunting relatives.

What does this mean? You can take the Lab out of hunting, but you can’t really take the “hunting” out of the Lab. It’s in there to some extent. More than 100 years of breeding have been focused on developing the ideal hunting dog, so just because people now desire the dog as a pet, doesn’t mean all these inherent abilities, intense drives and temperament traits simply go away. This in no way means the Labrador isn’t a great dog. In fact, if an owner knows what the inherent traits of a Lab are and how they could potentially affect home life when the Lab is strictly a pet (and not actively competing in the field or hunting on weekends), the owner will be better equipped to predict the impact of the new dog in his or her life. Knowing what to expect makes it easier for dog owners to determine if the Labrador Retriever is truly the dog for them.

Every breed has its benefits and challenges, and the Lab is no different in this aspect. There are qualities of the Labrador Retriever that makes him an incredible dog to own, and there are parts of this dog that can make him difficult to live within certain circumstances.

Whether the Lab is a good fit for you depends a lot on how highly you value the strong points of the breed versus how you handle the more challenging aspects of the breed. How you view the strengths and weaknesses of this breed depends on your lifestyle, your living situation, your expectations for a dog, and countless other factors. Only you can decide if the Labrador is a good choice for you.

To help you make up your mind, here’s a list of some of the good points of the breed and some of the facets of the Labrador that some dog owners have found a bit more challenging.

Pros:

There’s an awful lot of “good” going on with this breed. These are just a few of the Labrador Retriever’s finer points.

- Good-natured - The Lab is renowned for his congenial temperament. Easygoing and friendly, the Labrador is generally very stable in his temperament and often well suited for the novice owner to raise.

- Easy to Train - No dog trains himself: however, the Labrador Retriever is exceptionally bright and eager to please his owner, making him an ideal dog to work with on house manners and obedience skills.

- Athletic - If you’re looking for a dog to go jogging with, a hiking companion, or a breed that can partake in a variety of sports (both competitive and recreational), the healthy Labrador Retriever won’t disappoint.

- Family Dog - Some breeds are very much a one-person dog – they bond closely with one individual and may or may not be tolerant of other family members. The Lab tends to love his entire family.

- Low-maintenance Coat - The Labrador Retriever’s coat does not require expensive clips or professional grooming to maintain. If you can use a brush and don’t mind bathing him occasionally, you can keep a Lab’s coat in good shape.

- Swimmer Extraordinaire - Water activities are right up this dog’s alley. If introduced to water in a gentle manner, this breed is a great choice for a person who likes to spend time at the beach or lake.

- Dog-friendly - Successful hunting dogs must be able to get along with other dogs working in the field. This translates to a breed that typically isn’t dog aggressive.

- All-around Hunting Dog - The Labrador Retriever will retrieve on land and in water. A dog from hunting or “field” lines can make a terrific personal hunting companion.

- Loves People - With Proper socialization, the Labrador Retriever is very accepting of strangers and is more likely to show an intruder the way to the cookie jar than pin him in a corner.

- Good with Kids - The well-bred Labrador is quite tolerant (he’s not as easily offended as other breeds might be with an accidental bump or tug and can be a great companion for responsible children.

Challenges:

Many of the Labrador Retriever’s traits as a hunting dog can translate into higher demands as a house pet. None of these characteristics is insurmountable; however, they may require you to make a few adjustments in the home or to your lifestyle.

- High Exercise Requirements - The Labrador Retriever was bred to go all day in the field, hunting. The exercise demands of the Labrador from puppy through young adulthood and beyond (at least the first four years) are usually what shock new Lab owners the most. In general this dog will require a half hour to an hour of serious exercise at least twice a day.

- Demands Attention - The Lab was bred to work with, not independent of, a hunter. In a home, this translates to a dog that requires interaction with his owner. He will shadow you. He will bring you toys. He will even resort to inappropriate behaviors, if that’s what it takes to get your attention. Exercising (with you), training (with you), and attention (from you) will all help to keep our Labby happy.

- Mental Challenges - A smart dog is great for training, but an intelligent dog can become destructive if you don’t stimulate him mentally. Labs need to see new things, go to different places, and smell fresh scents. They need to learn new skills. If your Lab gets bored, he will try to find ways to entertain himself, and nice times out of ten, you won’t be entertained with what he comes up with…

- Destructiveness - If the Lab’s physical (exercise), mental (training), and emotional (attention) needs are not met, he tends to be quite destructive. Chewing everything, shredding pillows and furniture, digging trenches in the backyard, jumping the fence, and barking are just a few of the ways he’ll express himself.

- Slime - The Labrador is a great retriever. Some dogs have “wetter” or more slobbery mouths than others. If you’ve got a slobberer, you’ll find a nice, thick coat of slime on everything he chews or carries.

- Physical Players - The Lab has a very physical manner of play: Chasing, wrestling, and body slamming are typical maneuvers amount friendly, boisterous dogs. If you’ve got small children or older kids who tend to run and play hard themselves, you’ll need to take precautions to make sure that both dog and children know the rules and boundaries at playtime.

- Require Training - Because of the Labrador’s size and, shall we say, gusto for life, he is an exuberant companion. The Lab requires a good grounding in house rules and basic obedience commands just to keep him controllable when he’s happy and/or excited. Don’t forget, too, that the courage needed to dive unflinchingly into brambles, deep cover, and ice cold water can also translate into a dog with all family members, is usually all that is needed to maintain a healthy leadership relationship with the pet Lab.

- Bad Breeders - Whenever a dog hits the number one position in popularity, it is given that the breed’s naturally agreeable temperament will be corrupted by people who are more interested in how many puppies they can sell than how good a puppy they can produce. For this reason, a puppy buyer cannot assume that a puppy will have a tremendous temperament just because he is a Lab.

Statiscally, most dogs that wind up at shelters come from multi-pet households. Multi-pet households can be more challenging to manage, so before adding a dog to your home make sure you have the time, patience and commitment to make the situation work.

Needs a job – a dog that was bred for generations to perform a specific working function (in the case of the Labrador, hunting), requires regular mental and physical activity. This does not mean that you have to hunt your Labrador, but you will need to keep him busy.

The Labrador Retriever is the country’s most popular breed in large part because he makes such a good family dog. We place higher expectations on our dogs today than we did decades ago.

The job description of “family dog” has become more demanding than that of many true, working canine jobs.

The family dog is expected to be non-reactive to pokes, prods, and pinches from small children. He is expected to know when to welcome friends into the home and when to warn that a suspicious stranger is approaching. He is expected not to snap when someone falls on him or be protective of his toys, food, or crate. The family dog is to know his place in the family and never test the waters or try to move up in that ranking. Oh yes, and the family dog is expected to be accident-free in the house, play well with all dogs, and come when called.

There are dogs that fit this ideal. And, it’s pretty safe to assume that many of these dogs are Labrador Retrievers; however, a Lab doesn’t become the perfect family dog without help from his owner.

With that said, can the Labrador make a good family dog? ABSOLUTELY! The most common concern with Lab puppies and kids is the robustness of the puppy’s play. Of course, if the pup gets enough exercise and knows his basic commands, even this usually poses no problems. Labrador Retrievers have a natural affinity toward children, but that doesn’t make them automatically good with children – or vice versa, for that matter. Both dog and child need to be taught how to behave with each other, what is allowable and what is not.

A dog is the only thing on earth that loves you more than he loves himself.

- Josh Billings

The reason a dog has so many friends is that he wags his tail instead of his tongue.

- Anonymous

If there are no dogs in Heaven, then when I die I want to go where they went.

- Will Rogers

The average dog is a nicer person than the average person.

- Andy Rooney

We give dogs time we can spare, space we can spare and love we can spare. In return, dogs give us their all. It's the best deal man has ever made.

- M. Ackklam